The contemporary art scene is young, energized, rich,” says Lavar Munroe. “It’s beautiful to watch.” But he’s not talking about Berlin, or Brooklyn, or a hip part of Paris. Instead, the artist is referring to his own home of The Bahamas, and specifically Nassau, where he grew up in the Grants Town area. “People are really doing the work, and there’s a wonderful sculptural quality to it.”

If Munroe has his way — and he most probably will — by the end of this year, The Bahamas will be firmly on the art world’s radar. The 43-year-old is representing his country at the Venice Biennale — the biannual event that is the pinnacle of artistic exposure and runs from May to November — and he intends to do it proud. Not only is he taking 10 or 12 enormous canvases to the Italian city, and making some works in situ, he is also sharing the billing with another Bahamian artist, John Beadle, in a posthumous collaboration. Beadle died suddenly in 2024 at the age of 60. “When the curator of the Venice exhibition, Krista Thompson, proposed the idea [of the collaboration], I was really moved,” says Munroe, who knew Beadle well. “He was a mentor, not just to me, but to many back home. A very community-minded man.”

When I speak to Munroe, he is not drenched in Bahamian sunshine, but working in his huge studio in Baltimore, Maryland, where his two children both live and he spends half his time. The 2,000-square-foot space, in a converted cannery, is filled with light from 10-foot-tall windows and tables loaded with neatly arranged paint tubes and all sorts of materials: fabrics, feathers, plastic jerry cans and skeins of thread. “That’s all done by my two assistants,” he says with a laugh when I compliment the organization. A train track sits nearby — the hooting of locomotives fills the air — and the whole complex houses a buzzy mix of creativity, from florists, to motorbike builders, to artists and designers.

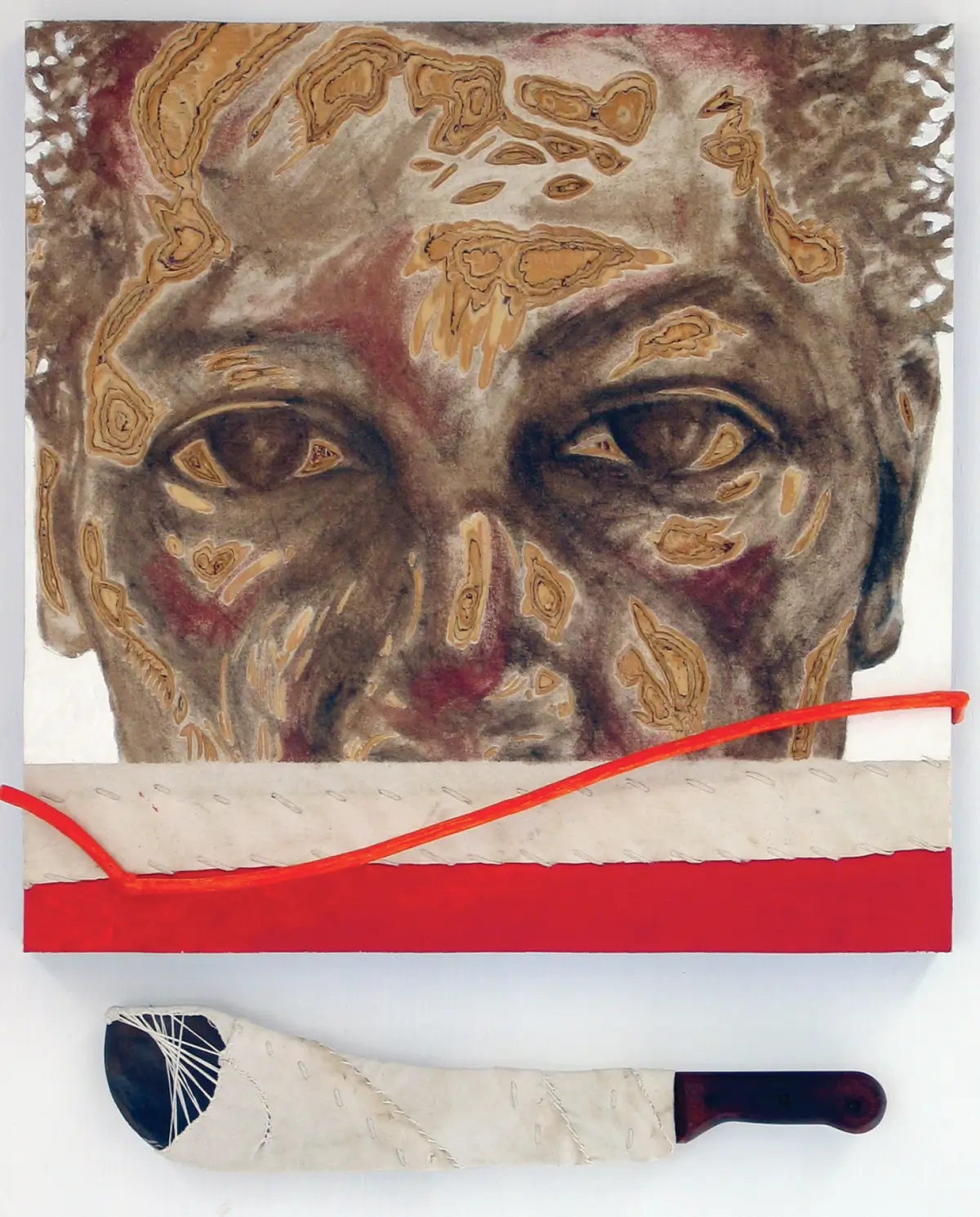

The Venice canvasses are taking shape around the walls. Large in scale, and unstretched, they show a procession of figures painted in acrylic, dressed in jeans and tunics and brightly colored trainers; they hold strings of real beads and wear silver crosses. One is taken up by a brilliant blue, white-waved sea.

All are speckled with rain. The subject is a Junkanoo wake, in which the spirits of the departed are sent back to the spirit world. “It’s in direct reference to John Beadle,” he says, pointing to the representations of many of Beadle’s sculptures in the piece: oars, machetes wrapped in sails, floating houses. “And the rain is important,” says Munroe. “If it starts to rain, it means you are connected to the spirit world.” Junkanoo is a Bahamian tradition, an exuberant carnival that usually takes place on Dec. 26 and Jan. 1, though preparation occurs all year. Munroe is steeped in its sensibilities, which go back to the times of slavery when the indentured were allowed a few days of freedom over Christmas. With reference to African spiritualism, Junkanoo can also send off the spirit “with libation and music and dance,” says Munroe, who has spent time in Africa studying ancestral ways.

The Junkanoo costumes and sculptures are created in so-called “shacks” — actually repurposed industrial hangars — by individual groups. “It’s tribal, like a fraternity,” says Munroe. “You are either born into one or signed into one. I am a Saxon. So is a former prime minister.” Inside the Junkanoo shack, there is no hierarchy. “Though the artists are the niche group,” says Munroe. “Apart from that, you’ll find doctors and lawyers and gangsters, all on the same level.” Costumes and props start with cardboard structures that gradually get more elaborate as they are passed down what is effectively an artistic assembly line. “You have the designer, then the builder; someone who draws the costume; the colorist; the paster who applies the paper, which is fringed; the decorator, who drops the gems and the feathers; and then the performer. It’s alchemy,” says Munroe.

[I’m] a tinkerer, who draws on wood and carves on paper.”

For many Bahamians, this is their art education, as Amanda Coulson, the executor of The Bahamas Pavilion in Venice, explains. “Caribbean kids learn from costume making, and in The Bahamas, at Junkanoo,” she says. “When you’re in school here, you don’t get given a box of crayons. We don’t have an art supply store. Our vernacular is not oil paint and watercolors.” Indeed, Beadle was also a great Junkanooer, who described himself as “a tinkerer, who draws on wood and carves on paper.” Where Beadle went on to complete his art education at the Rhode Island School of Design in the United States and became a great painter, Munroe studied at both the Savannah College of Art and Design and then at Washington University, both also in the United States.

“I worked as an illustrator for four years after I finished my BFA at Savannah,” says Munroe. “Then, in 2010, I was invited to the Liverpool Biennial. And I didn’t even know what a Biennial was. When I got there, it turned out my roommate was John Beadle. I became mesmerized by him and by the art world and decided to go back to college and be an artist.” There, Munroe started cutting and stabbing unstretched canvas with a knife, and then repairing it, to create rugged, fractured backgrounds, the legacy of which will be seen in Venice.

Munroe also took part in the 2015 Biennale in Venice, on the invitation of Okwui Enwezor, the much-loved Nigerian curator who died in 2019. “I was young, age-wise and artistically,” says Munroe. “I’ve grown tremendously since then.” Munroe’s father, to whom he was extremely close, couldn’t attend due to ill health and died the following year. “He had said he was never going to miss another of my exhibitions,” says Munroe. “So, in Venice, I will take a sculpture that represents him, a large red urn covered with small balls of clay in the African style and then covered in rope.” Munroe’s father was a parasailing instructor, and the rope and a large sculpture formed from a parachute that will also be on show, symbolize his presence. “It’s not a portrait; it’s an homage,” says Munroe.

His father also ensured that Munroe traveled from an early age. “It’s because of him I started going to Baltimore, and now it’s where I get most of my work done,” he says. “There are fewer distractions, and the studio is so big.” But The Bahamas is home, and Munroe’s small self-built studio there is surrounded by fruit trees — avocados, papayas and the little green fruits that Bahamians call guineps. There are wild chickens and roosters in the yard.

“No one comes here looking for art,” says Coulson, who has put together a private consortium to deliver the pavilion in Venice.

They come here for the sun. But we’re going to show the world what we’re capable of.”